France is out, who is in? African countries are building a new security order

After the military coup in Niger took place, new authorities refused to cooperate with France. At the same time, since August, active fighting has resumed in the north of Mali, where separatist organizations of Tuaregs, widely known as the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA), entered into open conflict with the government forces of Mali (FAMA).

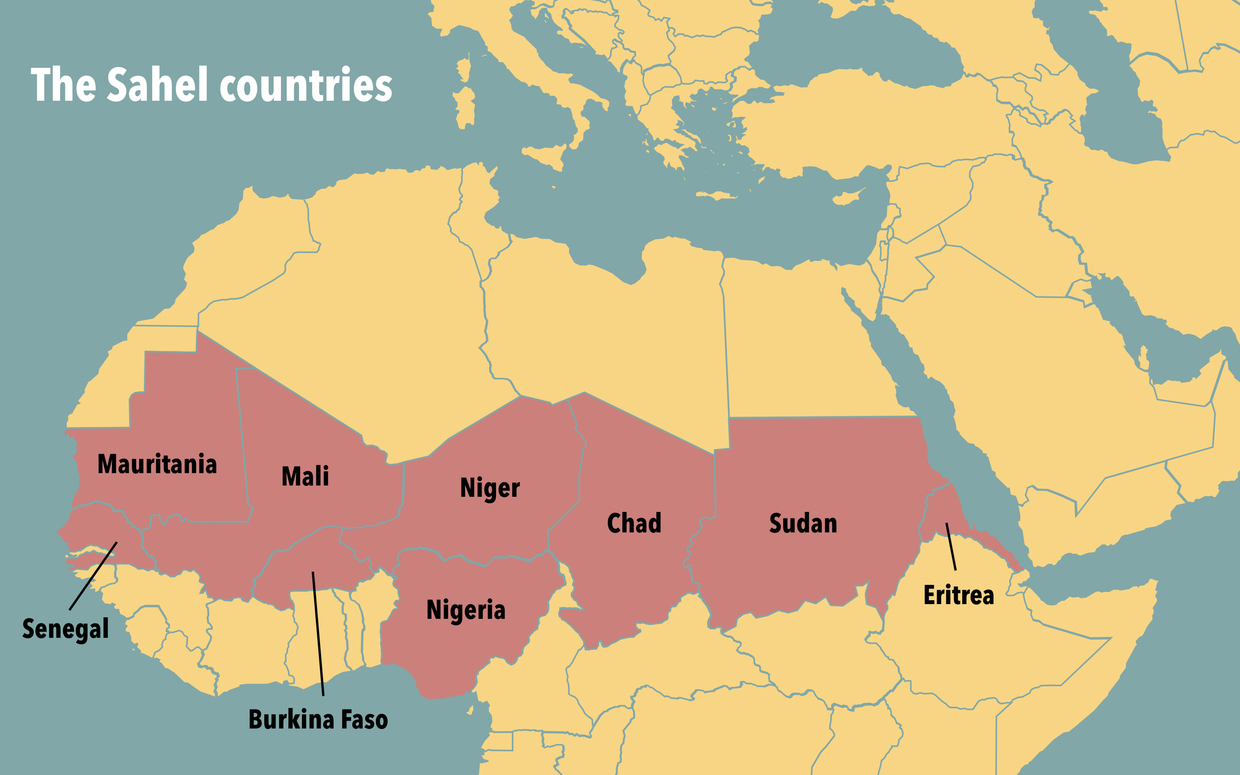

These events are taking place against the background of intensified attacks carried out by the third force – terrorist organizations in the Sahel region, in the area of three borders (Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso). All this raises the question, what is happening in the Sahel? And where will it all lead?

Background of the Mali crisis

Since 2015, the Algiers peace agreement, brokered by Algeria, the UN Multidisciplinary Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the African Union and the European Union, as well as the United States and France, have been in force in Mali. The agreements were supposed to end the military conflict that began in Mali in 2012 when movements largely composed of Tuaregs joined forces with Islamists to declare independence for Azawad, a historic region in northern Mali.

But the accords, essentially pushed by international mediators, have not been implemented by both sides. The rebel groups in the north were never disarmed, and of the 80,000 fighters who were part of the groups that signed the accords and were supposed to enter Mali’s armed forces, no more than 3,000 were integrated.

Moreover, the Algiers agreement actually divided the country into zones of influence. All this time, the northeastern Kidal region, part of the Timbuktu and Gao regions, remained under the control of the Tuareg movements. Government forces were not actively present in the area, entering it mainly for joint anti-terrorist operations with French forces.

French troops have been in Mali at the request of the Malian government since 2013 and led the anti-terrorist Operation Barkhane. A contingent of UN peacekeepers (MINUSMA) was also deployed in Mali, as was the Takuba multilateral initiative. Despite the international character of these missions, they were based mainly on the French perspective on security threats and thus also promoted French interests.

Over time, France’s intervention met with increasing criticism from both Malians and independent observers, as the French Army failed to address the issue of security in the country and terrorist attacks increased. In recent years, Mali has accused France of supporting the separatists, emphasizing that Paris has refused to provide active military assistance to Bamako to fight them.

Interestingly, the falsity of the French approach to the Sahel was also stated by former French ambassador to Mali (2002-2006) Nicolas Norman, who in 2019 stated: “The problem was that France then thought it could distinguish between good and bad armed groups. Some were perceived as political, and others as terrorists. And the French army went looking for this group – it was the Tuareg separatists from a particular tribe that was a minority among the Tuaregs themselves, the Ifoghas. We went after this group and gave them the town of Kidal. Then came the Algiers agreements, which put these separatists on a kind of pedestal, on an equal footing with the state. This is a major mistake.” All this kept the risk of further destabilizing Mali.

New conflict with Tuaregs

The military coup in Mali in May 2021, led by Colonel Assimi Goita, changed the balance of power in the country and the region. The new leadership, dissatisfied with the quality of French military assistance, shifted its focus to military cooperation with Russia the same year. French troops were forced to leave Mali.

Since the withdrawal of the French contingent from Mali in August 2022 and the launch of the MINUSMA withdrawal process (following a demand for the end of the mission from the authorities in Bamako), due to be completed in December 2023, old conflict lines have reopened in Mali. Mali’s central authorities are no longer willing to make any concessions and are seeking to regain complete control of the entire country, while the CMA wants to maintain its power in the north.

An intense stage of the conflict has arisen over the control of military bases left by MINUSMA. The contradictions are rooted in the 2014 ceasefire agreement, concluded on the condition that the forces remain in their current positions. Therefore, attempts by the Malian Armed Forces to occupy bases left by UN peacekeepers in areas controlled by Tuaregs are interpreted by CMA as a violation of the ceasefire. On the contrary, the Malian side believes that MINUSMA’s attempts to leave bases in the north of Mali before the deadline (the Malian armed forces’ ability to occupy them) are dictated by French interests and indicate a desire to transfer arms to local rebels to preserve a destabilizing influence.

Therefore, when the Malian army occupied a military base near the village of Ber in early August, it provoked fights with CMA. Armed clashes between the sides became increasingly frequent, and the central authorities occupied the Ber.

In early September, intense fighting took place near the town of Burem, and the Tuaregs declared that they were in a ‘time of war’ with the government of Bamako. During the Autumn, Tuareg forces attacked several Malian Army bases (Bourem, Lere, Diuri, Bamba) but never gained complete control of them. Government forces, in turn, almost without a fight, took control of the important town of Anefif, opening the way to the Tuareg rebel strongholds of Kidal, Aguelhok, and Tessalit. In late October, despite the rapid withdrawal of MINUSMA, the FAMA took control of the military base in Tessalit. On October 31, ahead of plan, MINUSMA left the military base in Kidal, occupied by Tuareg forces.

French Armed Forces Minister Sebastien Lecornu spoke about the current escalation in Mali: “The real news from now on in the Sahel will be the massive resurgence of the terrorist risk. Massive. This means potentially finding ourselves in a situation where Mali could be partitioned in the coming weeks or months.” Obviously, such statements are perceived extremely negatively in Bamako, which considers them as evidence of direct influence on events from Paris.

Terrorist threat growing

In recent years, the Sahel has witnessed a series of military coups (Mali in 2020 and 2021, 2 coups in Burkina Faso in 2022, and Niger in 2023) that brought to power the military leaders who were dissatisfied with security problems and had anti-French views. Thus, in early 2023, the authorities of Burkina Faso, following Mali, demanded that Paris withdraw its troops from their territory. All this undermined France’s regional interests, gradually undermining its traditional dominant position.

The latest example of this trend was Niger, where the authorities, who came to power as a result of a military coup that Paris condemned, demanded the withdrawal of the French contingent from the country and declared the French ambassador as persona non grata. Despite the threat of an ECOWAS invasion into Niger and a two-month political standoff, France launched the process of withdrawing its troops from Niger in early October.

Notably, the events in Niger and the French loss of influence did not affect American interests. Since Washington took a neutral position by taking diplomatic initiatives and did not condemn the military coup, it was able to maintain its military presence in the country.

Other institutions built around France continue to disintegrate in the region. The Paris-backed Group of Five (G-5), consisting of Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mauritania, operated in the Sahel since 2014. The format aimed to coordinate efforts to combat the terrorist threat but never became an influential regional institution.

Mali, in May 2022, became the first state to announce its withdrawal from the G-5, in effect cutting the group’s territorial connectivity. The ensuing end of military cooperation with France by Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, and the withdrawal of French forces from these countries, finally put an end to the G-5’s activities, as only two states (Mauritania and Chad), located at the eastern and western “poles” of the region, remained ready to engage with France.

Despite the withdrawal from French control, security threats in these countries continue to grow. In Niger, a group of Tuareg who disagreed with the military coup announced the creation of a Council of Resistance for the Republic to restore the overthrown president to power. Still, no concrete action has yet been taken. The Mali central government’s conflict with the Tuaregs has diverted Mali’s forces from fighting the terrorist threat, while attacks by jihadist organizations continue in Mali: JNIM (Jamaat Nasrat al-Islam wal Muslimin, the local branch of al-Qaeda) is besieging Timbuktu, the most important city in central Mali, and attacking both Malian army military bases and civilian targets. “Wilayat Sahel” (the local branch of the Islamic State) took over vast territories in the Menaka region in eastern Mali (the Three Borders area) as early as April 2023, triggering a large-scale exodus of refugees from the region, and continues to carry out attacks in the country.

The activity of radical terrorist organizations has also increased in other Sahel states. In recent months, major deadly attacks have occurred in Niger near the border with Mali, and attacks on the army have occurred in northwestern Burkina Faso, where the local IS branch still controls much of the northern region of that country.

This situation, as well as the threat to the military regimes, forces the authorities to seek new cooperation formats. On September 16 of this year, the leaders of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger signed the Liptako-Gourma Charter (the name of the Three Borders area), creating the Alliance des Etats du Sahel (Alliance of States of the Sahel).

Since the creation of the alliance took place amid the Malian government’s conflict with rebels and the threat of an ECOWAS invasion in Niger, it was particularly important in the agreement to include a collective defense mechanism in the event of an attack on one of its members, which strengthened the power of the military regimes.

It is also worth noting that the agreement was signed the day after a delegation from the Russian Defense Ministry visited Bamako, which might suggest that preliminary consultations with Moscow were held. In the short period after the alliance was established, its members have already announced joint operations against terrorist groups along the three borders.

What to expect

The regional security structure in the Sahel is changing significantly. France’s traditional dominance, backed by a broad military presence and collective international initiatives, although declining, still retains opportunities for Paris to influence local governments. The breakdown of previous cooperation formats does not yet solve regional problems. The Sahel continues to face critical challenges, including the jihadist threat, internal fragmentation, and conflict, leaving states in the region extremely fragile and interested in finding international partners willing to help manage these challenges.

A new security structure that is beginning to emerge in the Sahel provides competitive opportunities for external involvement by both regional powers (e.g., Algeria) and non-regional powers (Russia, Turkey). The effectiveness (or lack thereof) of the new regional alliance, which already demonstrates the more subjective nature of the states in the region, will also play a central role in shaping the new security structure.

The central authorities in the Sahel countries still lack a monopoly on the use of force. Therefore, legitimacy crises and transfer of power problems are intensifying, resulting in violent struggles to retain influence and access to resources (as clearly seen in the renewed Tuareg crisis in northern Mali). The transition period will continue to be accompanied by growing security threats and expansion of conflict zones, and the Sahel states must figure out how to overcome it.

Therefore, the current conflict in Mali becomes particularly crucial. It is expected that the Bamako authorities will keep trying to break the armed resistance of the Tuaregs and will continue their campaign in the north, using their air advantage. However, the battle for control of military bases and towns under Tuareg rule since 2013 will be tougher. It may appeal to regional allies of both sides, as it will prove decisive in the distribution of power within Mali and the region for the coming years.